Author: Tyler Phillips, Research Psychologist and Lead Content Specialist

One of the great ironies of humanity’s current era is the simultaneous growth of our connectedness as well as our disconnectedness. Technological evolution is proliferating the number of ways and tools with which we are in constant virtual contact with each other. At the same time, simply being in contact does not automatically provide us with the substance of genuine connection. In fact, a sense of emotional isolation is also growing among us, so much so that the US Surgeon General recently declared loneliness a major public health crisis.

In response, one of the possible solutions that is gaining much attention, including in the workplace, is to rekindle and reprioritize empathy. This capacity is the bridge to that genuine connectedness, whether it be cognitive empathy (understanding another’s thoughts and point of view; ‘thinking in their shoes’) or affective empathy (identifying with and relating to another’s emotions; ‘feeling in their shoes’).

Indeed, empathy has been put forward as the most important skill for leaders to develop. Yet, while empathy has also been emphasized as a must-have business strategy, implying a need for group effort in an organization, the suggestions for its cultivation still seem to focus on the actions of a single leader. There is an important distinction between the capacity of one person to behave empathetically, and the capacity of a group of people to engage with each other empathetically — in other words, between individual-level empathy and collective-level empathy. It appears that the distinction isn’t sufficiently addressed, and in order to create a truly empathetic system — an empathetic organization — it should be.

In light of this, we were interested in investigating how individual-level and group-level empathy seem to work in terms of individual resilience. Indeed, each of these two levels of empathy is important for our ability to adapt to changes, overcome stressors, and learn in the process. Additionally, in terms of combating the sense of emotional isolation, it is affective empathy, as opposed to cognitive empathy, that is arguably more relevant. In a one-on-one relationship, when we accurately feel what another is feeling, we can offer responses and supportive actions that are more in tune with what they really need. This enables their adaptability, and also makes them more likely to return that empathetic regard to us when we need it. In a team, when everyone is good at relating to each other’s emotions, and works collaboratively with that consideration when making decisions, then the adaptability of the whole group is strengthened. In the Neurozone system, we call this team dynamic ‘empathetic response style’.

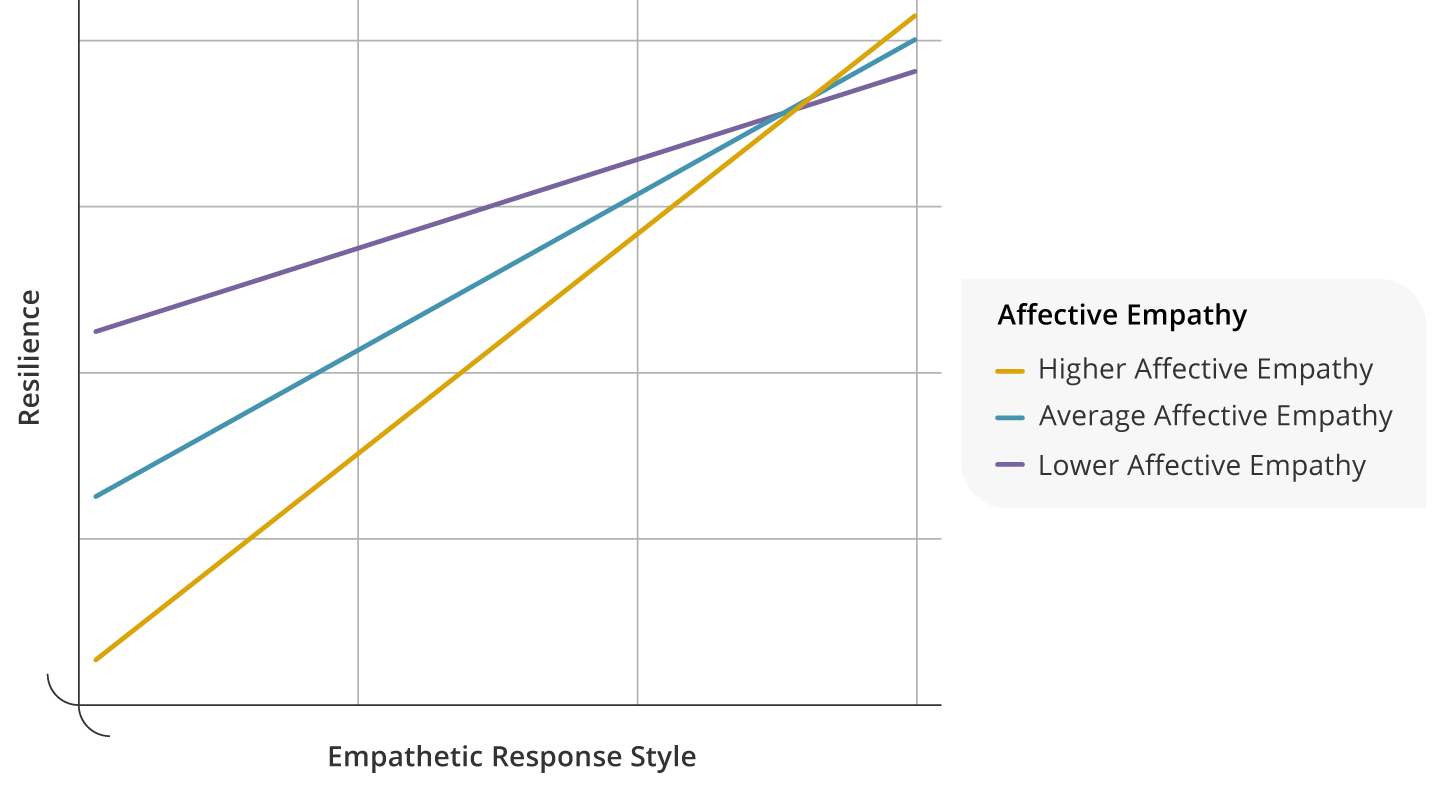

So, we analyzed our data regarding affective empathy and empathetic response style to uncover the nature of their relationship in enhancing resilience (as measured by our NRI). This data comes from more than 550 individuals, with a mixed gender distribution, a broad age range, and a spread across 18 different industries. What we found is this: affective empathy interacts with empathetic response style to predict resilience. Consider the graph below:

In this graph, the yellow line represents individuals with higher affective empathy, the blue line represents individuals with average affective empathy, and the purple line represents individuals with lower affective empathy. These lines show that, when the empathetic response style in the team is low (bottom left), individuals with higher affective empathy are less resilient compared to their peers with lower affective empathy. However, when the team dynamic starts to become more empathetic (in members' interactions with and responses to one another), individuals with higher affective empathy begin to surpass individuals lower in affective empathy in their resilience (as indicated by the crossover of the lines on the graph). In other words, when the team is characterized by a high empathetic response style (top right), individuals high in affective empathy tend to be more resilient than those with lower affective empathy.

What does the graph actually show in terms of empathy and resilience? First, bear in mind that resilience represents a capacity to respond optimally to stress, which includes returning to or remaining in a parasympathetic state (of ‘rest-and-digest’) in situations where the stress response (or sympathetic state of ‘fight-or-flight’) is not necessary. If an individual high in affective empathy is in a group where the overall dynamic of interaction is non-empathetic, then that is unlikely to promote a stress-free state. They may be good at feeling others’ feelings, but those others may not be good at responding as if they are feeling that person's feelings in return. An empathetic individual may have the capacity to meet others’ connective needs, but others seem like they can’t, or don’t, adequately meet theirs. This incongruence between their own nature and the nature of the team environment may therefore be registered in their nervous system as a stressor, or a potential threat for emotional isolation, and so it may move them into sympathetic or stress activation — and possibly lower their resilience.

In contrast, for those who are lower in affective empathy, the incongruence between their own nature and that of the team is relatively lower. Because their own empathy levels and those of the team are more aligned — even though they are both low — suboptimal empathetic response style may not register as strongly as a stressor or potential threat. This seems to be why their resilience is not as taxed compared to those with higher affective empathy.

However, when the team as a whole engages more empathetically, the incongruence between individual- and group-level empathy is reassigned. Individuals who are high in affective empathy are now more aligned with the empathetic way of responding that characterizes the larger group, while individuals with lower affective empathy are less aligned with it. A high empathetic response style in the team will benefit everyone, since the collective is more in tune with any one individual’s emotional state — hence, resilience rises for all. However, those who are not so good at pulling their own empathizing weight will not achieve as big a resilience boost as those who are really good at it.

In summary, these results show that high affective empathy coupled with high levels of empathetic response style in a team is what leads to optimum resilience in the sample we studied. Returning to the matter of organizational dynamics, it is therefore in the best interests of everyone that steps are taken to enhance (or facilitate the enhancement of) both individual-level empathy and team-level empathy. Through the cultivation of both, emotional isolation may be combatted, the paradox of (dis)connectedness may be attenuated, and the resilience of the entire system may be enhanced most strongly.